Li-ion battery materials: present & future

- Nitta, N., Wu, F., Lee, J. T., & Yushin, G. (2015). Li-ion battery materials: present and future. Materials today, 18(5), 252-264.

Abstract

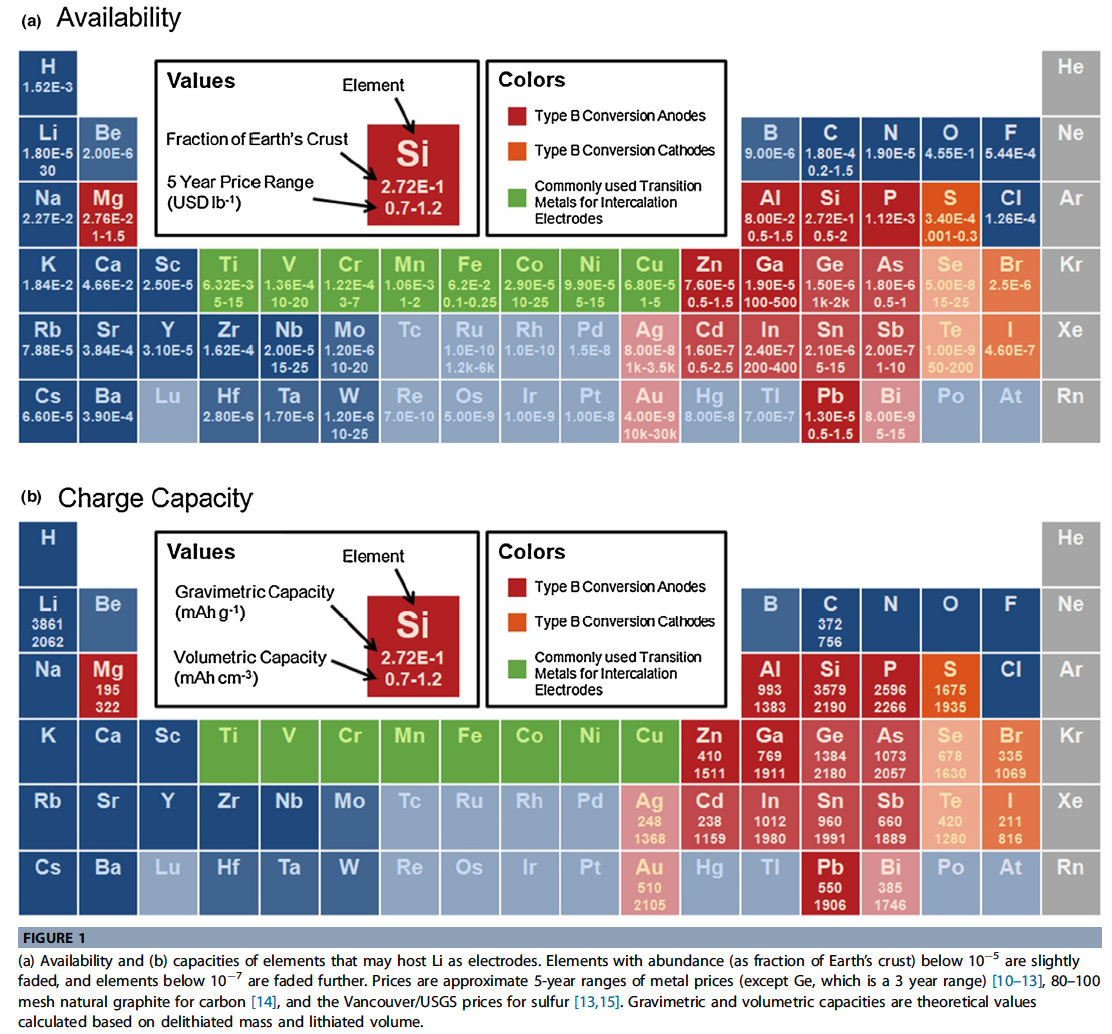

- This review covers key technological developments and scientific challenges for a broad range of Li-ion battery electrodes materials : lithium cobalt oxide (LCO), lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide (NCM), lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide (NCA), lithium iron phosphate (LFP), lithium titanium oxide (LTO) and others are contrasted with that of conversion materials, such as alloying anodes (Si, Ge, Sn, etc.), chalcogenides (S, Se, Te), and metal halides (F, Cl, Br, I). The cost, abundance, safety, Li and electron transport, volumetric expansion, material dissolution, and surface reactions for each type of electrode materials are described

Introduction

- Li-ion batteries are costly at present, and a shortage of Li and some of the transition metals currently used in Li-ion batteries may one day become an issue.

- At the same time, Li-ion batteries have certain fundamental advantages over other chemistries.

- Li has the lowest reduction potential of any element, allowing Li based batteries to have the highest possible cell potential

- Li is the third lightest element and has one of the smallest ionic radii of any single charged ion. These factors allow Li-based batteries to have high gravimetric and volumetric capaci- ty and power density.

- Although multivalent cations allow for higher charge capacity per ion, the additional charge significantly reduces their mobility.

- In terms of absolute quantities, the amount of Li available on the Earth’s crust is sufficient to power a global fleet of automobiles.

- Li is not a major factor in the cost of Li-ion batteries at present. Li is used in the cathode and electrolyte, which make up only a small portion of the overall cost. Within these components the cost of processing and the cost of cobalt in cathodes are the major contributing factors

- Electrodes with higher rate capability, higher charge capacity, and (for cathodes) sufficiently high voltage can improve the energy and power densities of Li batteries and make them smaller and cheaper. However, this is only true assuming that the material itself is not too expensive or rare.

- Mn is clearly much cheaper than Co, P and S are much more abundant than the more conductive elements in Groups V and VI, respectively.

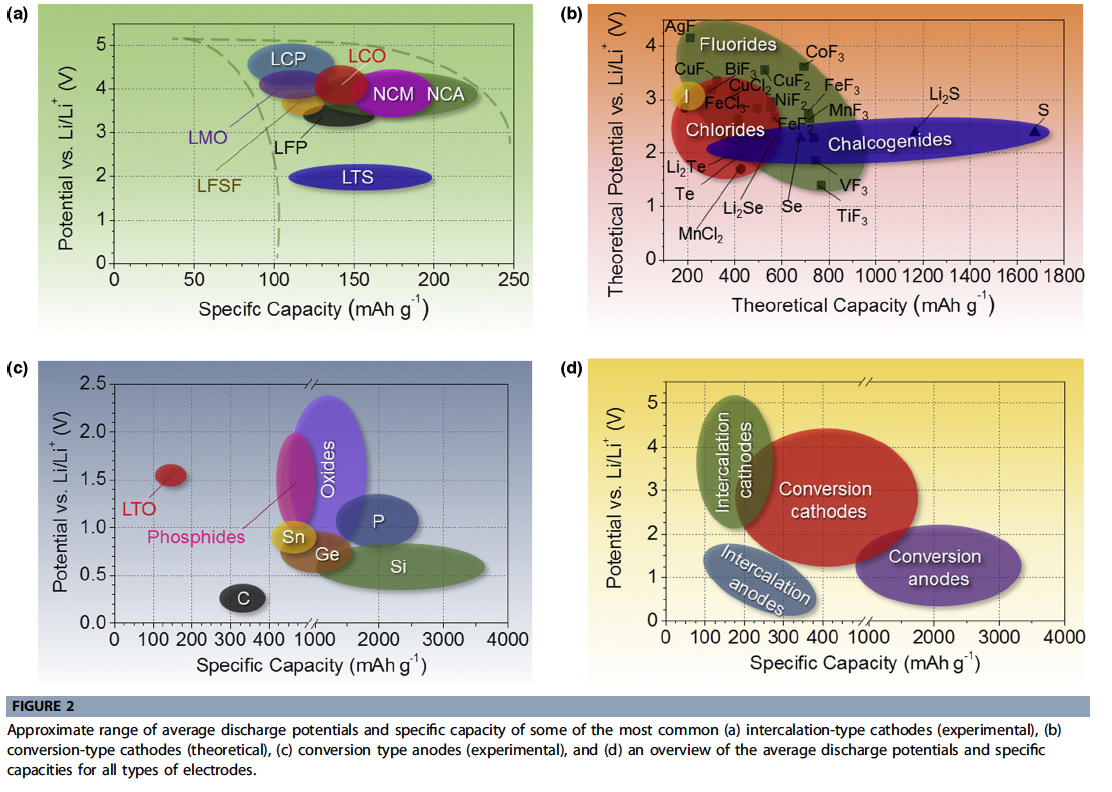

- Figure 2 is a fairly comprehensive form of a popular chart, depicting average electrode potential against experimentally accessible (for anodes and intercalation cathodes) or theoretical (for conversion cathodes) capacity.

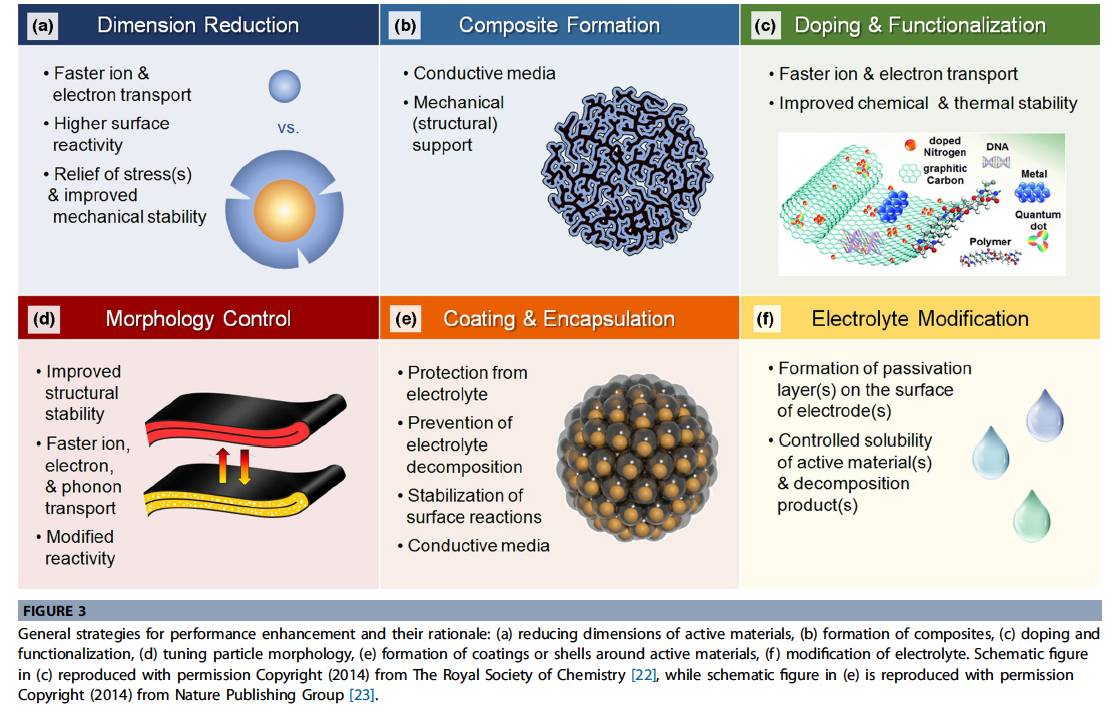

- To enable the application of new types of electrode materials, various strategies have been used. These strategies are summarized in Fig. 3, and are often similar regardless of type of material, crystal structure, or operating mechanism.

Cathodes

Intercalation Cathode Materials

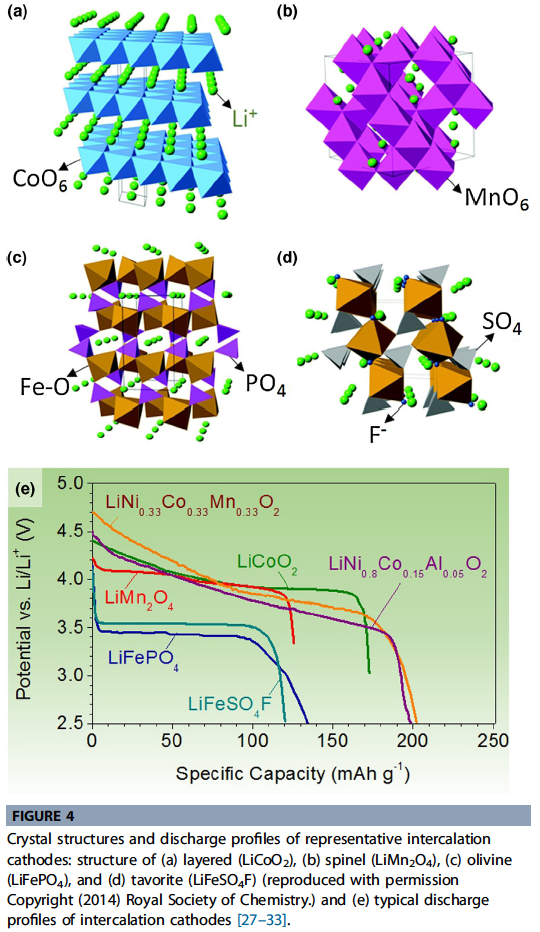

- An intercalation cathode is a solid host network, which can store guest ions. The guest ions can be inserted into and be removed from the host network reversibly. In a Li-ion battery, Li+ is the guest ion and the host network compounds are metal chalcogen-ides, transition metal oxides, and polyanion compounds.

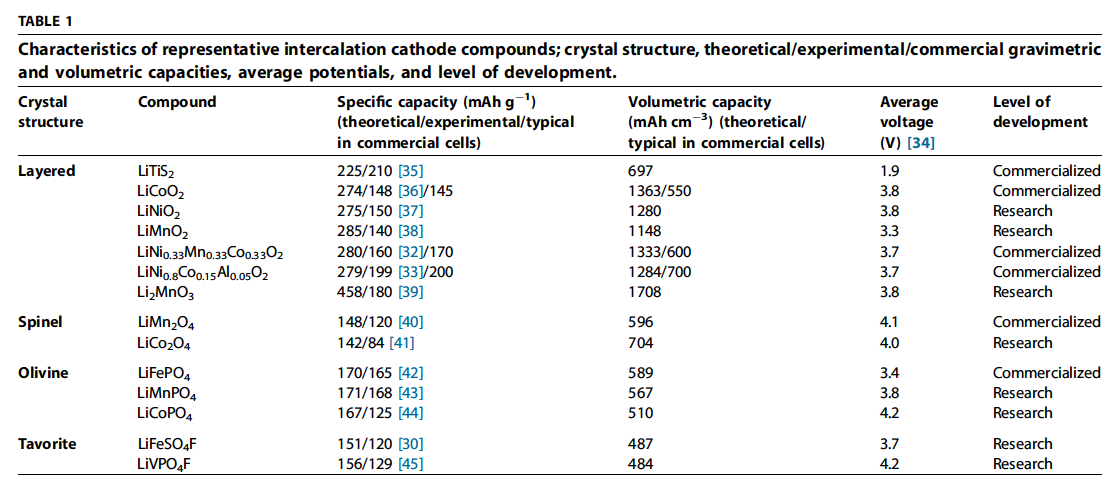

- These intercalation compounds can be divided into several crystal structures, such as layered, spinel, olivine, and tavorite.

- The layered structure is the earliest form of intercalation compounds for the cathode materials in Li-ion batteries. Metal chalcogenides including \(TiS_3\) and \(NbSe_3\) were studied long ago as a possible intercalating cathode materials.

- While \(TiS_3\) exhibited only partial reversibility due to irreversible structure change from tri-gonal prismatic to octahedral coordination on lithiation, \(NbSe_3\) demonstrated reversible electrochemical behavior.

- \(LiTiS_2\) (LTS) was widely studied due to its high gravimetric energy density combined with long cycle life (1000+ cycles) and was eventually commercialized by Exxon.

- Most current intercalation cathode research is focused on the transition metal oxide and polyanion compounds due to their higher operating voltage and the resulting higher energy storage capability.

- Typically, intercalation cathodes have 100–200 mAh/g specific capacity and 3–5 V average voltage vs. Li/Li+ (Fig. 4e, Table 1).

Transition metal oxide

- \(LiCoO_2\) (LCO) introduced by Goodenough is the first and the most commercially successful form of layered transition metal oxide cathodes. The Co and Li, located in octahedral sites occupy alter-nating layers and form a hexagonal symmetry (Fig. 4a).

- LCO is a very attractive cathode material because of its relatively high theoretical specific capacity of 274 mAh g1, high theoretical volumetric capacity of 1363 mAh cm3, low self-discharge, high dis-charge voltage, and good cycling performance.

- The major limitations are high cost, low thermal stability, and fast capacity fade at high current rates or during deep cycling. LCO cathodes are expensive because of the high cost of Co (Fig. 1). Low thermal stability refers to exothermic release of oxygen when a lithium metal oxide cathode is heated above a certain point, resulting in a runaway reaction in which the cell can burst into flames.

- LCO typically experiences thermal runaway past \(~200^oC\) due to an exothermic reaction between the released oxygen and organic materials.

- Deep cycling (delithiation above 4.2 V, meaning approximately 50% or more Li extraction) induces lattice distortion from hexagonal to monoclinic symmetry and this change deteriorates cycling performance.

- Many different types of metals (Mn, Al, Fe, Cr) were studied as dopants/partial substitutes for Co and demonstrated promising but limited performance.

- Coatings of various metal oxides \(Al_2O_3, B_2O_3, TiO_2, ZrO_2\) were more effective in enhancing LCO stability and performance characteristics even during deep cycling, because mechanically and chemically stable oxide material could reduce structural change of LCO and side reactions with electrolyte.

- \(LiNiO_2\) (LNO) has same crystal structure with \(LiCoO_2\) and a similar theoretical specific capacity of 275 mAh g1. Its relatively high energy density and lower cost compared to Co.

- However, pure LNO cathodes are not favorable because the Ni2+ ions have a tendency to substitute Li+ sites during synthesis and delithiation, blocking the Li diffusion pathways.

- LNO is also even more thermally unstable than LCO because Ni3+ is more readily reduced than Co3+

- Insufficient thermal stability at high state-of-charge (SOC) can be improved via Mg doping, and adding a small amount of Al can improve both thermal stability and electrochemical performance.

- As a result, the \(LiNi_{0.8}Co_{0.15}Al_{0.05}O_2\) (NCA) cathode has found relatively widespread commercial use, for example, in Panasonic batteries for Tesla EVs. NCA has high usable discharge capacity (200 mAh g1) and long storage calendar life compared to con-ventional Co-based oxide cathode.

- However it was reported that capacity fade may be severe at elevated temperature (40–70C) due to solid electrolyte interface (SEI) growth and micro-crack growth at grain boundaries.

- \(LiMnO_2\) (LMO) can also be promising because Mn is much cheaper and less toxic compare to Co or Ni.

- However, the cycling performance of LMO was still not satisfactory (i) because the layered structure has a tendency to change into spinel struc-ture during Li ion extraction and (ii) because Mn reaches out of LMO during cycling.

- Mn dissolution occurs when Mn3+ ions undergo a disproportionation reaction to form Mn2+ and Mn4+, and this process is observed for all cathodes containing Mn. Mn2+ is thought to be soluble in the electrolyte, and destabilize the anode SEI. Also, the anode impedance is seen to increase with Mn dissolution on carbon anodes, but not LTO (which has a negligible SEI).

- the poor cycle stability of LMO (especially at elevated temperatures) has hindered widespread commercialization.

- \(Li(Ni_{0.5}Mn_{0.5})O_2\)(NMO) could be an attractive material because it can maintain similar energy density to LCO, while reducing cost by using lower cost transition metals. The presence of Ni allows higher Li extraction capacity to be achieved. However, cation mixing can cause low Li diffusivity and may result in unappealing rate capability.

- Recent ab initio computational modeling predicted that low valence transition metal cations (Ni2+) provides high-rate pathways and low strain, which are the crucial factors to achieve high rate capability in layered cath-odes.

- \(LiNi_xCo_yMn_zO_2\) (NCM, NMC) has similar or higher achievable specific capacity than LCO and similar operating voltage while having lower cost since the Co content is reduced.

- \(Li_2MnO_3\) stabilized \(LiMO_2\) (where M = Mn, Ni, Co) can also achieve high capacity (>200 mAh g1) under high voltage operation (4.5–3.0 V). It is also activated at >4.5 V, releasing \(Li_2O\) on the initial cycle which provides extra Li+. The remaining \(Li_2MnO_3\) can also facilitate Li diffusion and also act as a Li reservoir. It is called lithium-rich layered oxide compound.

- \(LiNi_{0.68}Co_{0.18}Mn_{0.18|O_2\), in which each particle consists of bulk material surrounded by a concentration-gradient outer layer was reported.

- The bulk material is a nickel-rich layered oxide \(LiNi_{0.8}Co_{0.1}Mn_{0.1}O2\) for higher energy/power density (higher Ni content allows for higher Li extraction without structure deterioration), while the outer layer is Mn and Co substituted NMC \(LiNi{0.46}Co_{0.23}Mn_{0.31}O_2\) for better cycle life and safe.

- It is pro-posed that the stability of this material could originate from stable Mn4+ in the surface layer, hence the gas evolution due to reaction between Ni ion and electrolyte is delayed.

- Spinel \(Li2_Mn_2O_4\) (also LMO) [82] benefits from the abundance, cost, and environmental friendliness of Mn. The insufficient long-term cyclability is believed to originate from irreversible side reactions with electrolyte, oxygen loss from the delithiated \(LiMn_2O_4\), Mn dissolution, and formation of tetragonal \(Li_2Mn_2O_4\) at the surface especially at the fast c-rates.

- By using nanoparticles, the rate performance can be greatly improved due to shorter Li+ diffusion lengths and im-proved electronic transport.

- Although decreased diffusion lengths also exacerbates the dissolution problem, it can be repressed with a surface coating of ZnO , Mn-rich layered structure, metal doping, oxygen stoichiometry blending with different cathode materials, and forming a stable cathode SEI layer.

Polyanion Compounds

- Large \(XO_4^{3-}\) (X = S, P, Si, As, Mo, W) polyanions occupy lattice positions and increase cathode redox potential while also stabilizing its structure.

- \(LiFePO_4\) (LFP) is the representative material for the olivine structure, known for its thermal stability and high power capability. In LFP, Li+ and Fe2+ occupy octahedral sites, while P is located in tetrahedral sites in a slightly distorted hexagonal close-packed (HCP) oxygen array (Fig. 4c).

- The major weaknesses of the \(LiFePO_4\) cathode include its relatively low average potential (Fig. 4e, Table 1) and low electrical and ionic conductivity

- Reduction in particle size in combination with carbon coating and cationic doping were found to be effective in increasing the rate performance. It is noteworthy that good electrochemical performance can also be achieved without carbon coating if particles are uniformly nano-sized and conductive nanocarbons are used within the cathodes.

- In general, however, the low density of nanostructured LFP electrodes and their low average potential limit the energy density of LFP cells.

- Other olivine structures include \(LiMnPO_4\) (LMP) which offers 0.4 V higher average voltage compared to olivine LFP (Table 1), leading to higher specific energy, but at the expense of lower conductivity. \(LiCoPO4, LiNi{0.5}Co_{0.5}PO4, and LiMn{0.33|Fe_{0.33-}Co_{0.33}PO_4\) (LCP, NCP, MFCP) are also developed.

- \(LiFeSO_4F\) (LFSF) is yet another interesting cathode material because of its high cell voltage and reasonable specific capacity (151 mAh g-1). Fortunately LiFeSO4F has better ionic/elec-tronic conductivity hence it does not desperately need carbon coating and/or nanoparticles. LiFeSO4F can also be economical since it can be prepared with abundant resources.

- The vanadium-containing material, \(LiVPO_4F\), cycles well, and has high voltage and capacity but raise concerns about toxicity and environmental impact. Interest-ingly, Li+ can be intercalated at 1.8 V hence this material is able to be used in both anode (Li1+xVPO4 where x = 0–1) and cathode (Li1xVPO4 where x = 0–1).

Conversion Cathode Material

- Conversion electrodes undergo a solid-state redox reaction during lithiation/delithiation, in which there is a change in the crystalline structure, accompanied by the breaking and recombining chemical bonds.

\[ Type\ A\quad MX_z+yLi<→M+zLi_{y/z}X\quad(1)\\Type\ B\quad yLi+X<→Li_y X\quad (2) \]

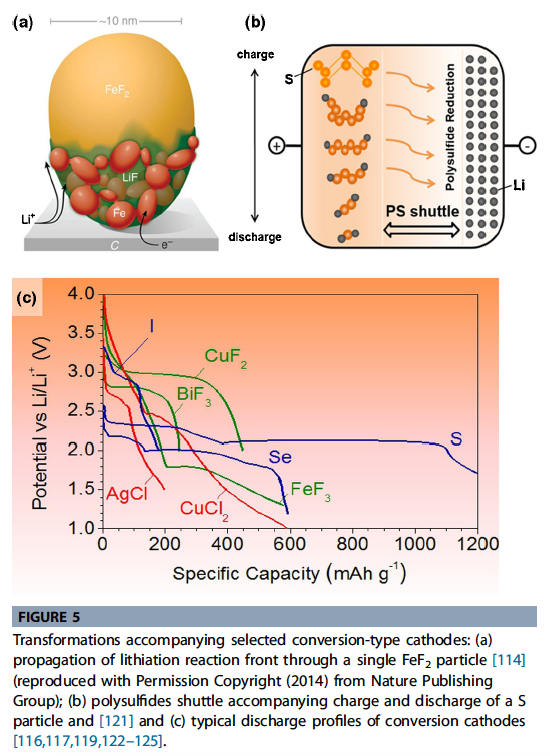

- For cathodes, the Type A category (Eq. (1)) includes metal halides comprising high (2 or more) valence metal ions to give higher theoretical capacities. The F ions, having the higher mobility, diffuse out of the \(FeF2\), and form LiF while nanosized phases of Fe form behind it [115]. This results in metal nanoparticles scattered in a ‘sea’ of the LiF \(Li{y/z}X\) from Eq. (1)).

- Figure 5a shows how this reaction takes place for FeF2 particles.

- S, Se, Te, and I follow the Type B reaction (Eq. (2)). Of these elements, S has been studied the most because of its high theoreti-cal specific capacity (1675 mAh g1), low cost, and abundance in the Earth’s crust. Oxygen is also a Type B cathode in lithium air batteries, but poses fundamentally different technological hurdles because it is a gas.

- Figure 5b shows the intermediate steps for the full S conversion reaction, which involves intermediate polysulfides soluble in organic electrolytes. Figure 5c shows the typical discharge curves of conversion cathodes.

Fluorine & Chlorine Compounds

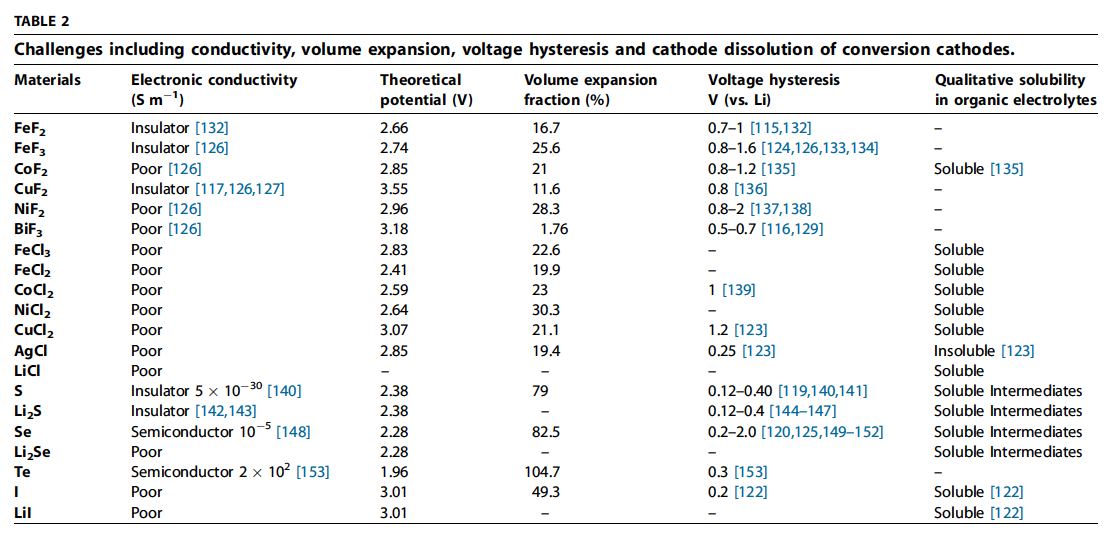

- Metal fluorides (MF) and chlorides (MCl) have recently been actively pursued due to intermediate operation voltages and high theoretical specific and volumetric capacities. However, MF and MCl generally suffer from poor conductivity, large voltage hysteresis, volume expansion, unwanted side reactions, and dissolution of active material (Table 2). However their open structures can support good ionic conduction.

- All of the reported MF and MCl materials show very high voltage hysteresis for reasons such as poor electronic conductivity and ion mobility (Table 2).

- Many ionic compounds are soluble in polar solvents, and this is true for some fluorides as well. Metal chlorides (including LiCl) are even more susceptible to dissolution in various solvents, including those that are used in Li battery electrolytes . Meanwhile, the volume expansions of MF and MCl, as calculated by using room temperature densities of compounds before and after lithiation, are somewhat moderate (Table 2).

- In order to overcome their low conductivities, synthesis of nanoparticles of conversion materials is essential to shortening the pathway for the electrons and ions.

- Electrolyte modifications are also important to minimize unfavorable reactions between the electrolyte and active material during various stages of charge and discharge.

Sulfur & lithium sulfide

- Sulfur has an extremely high theoretical capacity at 1675 mAh g1, while also being low cost and abundant in the Earth’s crust.

- However, S based cathodes suffer from low potential vs. Li/Li+, low electrical conductivity, dissolution of intermediate reaction products (polysulfides) in electrolyte, and (in the case of pure S) very low vaporization temperature, which induces S loss while drying the electrodes under vacuum. Sulfur al**so suffers from 80% volume change **, which may destroy the electrical contact in standard carbon composite electrodes

- To mitigate the effects of both dissolution and volume expansion, S can be encapsulated in a hollow structure with excess internal void space.

- To avoid the negative effects of expansion, prevent S evapora-tion during drying, and form full cells with Li free (and thus safer) anodes, electrodes have also been fabricated in the form of \(Li_2S\). \(Li_2S\) is not easily infiltrated into a host as with S because it has a much higher melting point.

- The high solubility of Li2S in various environmentally friendly solvents (such as ethanol) can be utilized to form various Li2S based nanocomposites. Because the fully lithiated Li2S does not expand any further, no void spaces are necessary.

- Electrolyte modification is a popular method for mitigating polysulfide dissolution (Fig. 3f). \(LiNO_3\) and \(P_2S_5) additives were used to form good SEI on the surface of Li metal to prevent the reduction and consequent precipitation of polysul-fides.

Selenium & Tellurium

- Recently, Se and Te have attracted attention due to their higher electronic conductivities than S and high theoretical volumetric capacities of 1630 mAh cm3 and 1280 mAh cm3, respectively. Due to the higher electronic conductivity, Se and Te often show higher utilization of active materials and higher rate capability than S.

- Similar to S, the Se-based cathodes suffer from the dissolution of high-order polyselenides resulting in fast capacity loss, poor cycle performance and low coulombic efficiency. Fortunately, Se and Te are also similar to S in that they have low melting points.

- However, Te is far too expensive for practical use. Moreover, Se and Te are of similar abundance as Ag and Au (Fig. 1), and are very unlikely to be used in mass production.

Iodine

- The lithium-iodine primary battery uses LiI as a solid electrolyte (109 S cm1), resulting in low self-discharge rate and high energy density, and is an important power source for implantable cardiac pacemaker applications

- However, it has low power capability. Organic electrolytes, iodine, triodide, and lithium iodide are all soluble.

Anode

- Anode materials are necessary in Li-ion batteries because Li metal forms dendrites which can cause short circuiting, start a thermal run-away reaction on the cathode, and cause the battery to catch fire.

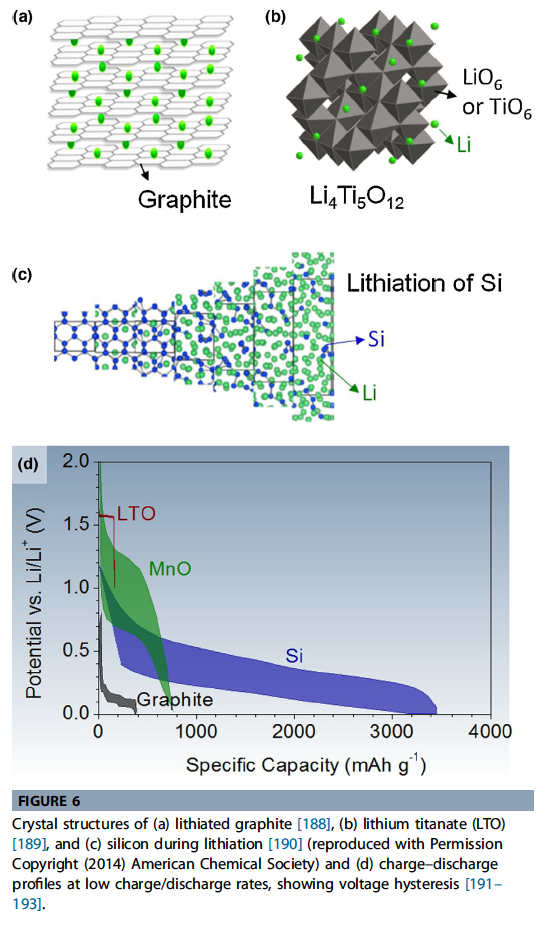

Graphine & Hard Carbons

- Electrochemical activity in carbon comes from the intercalation of Li between the graphene planes, which offer good 2D mechanical stability, electrical conductivity, and Li transport (Fig. 6a). Up to 1 Li atom per 6 C can be stored in this way.

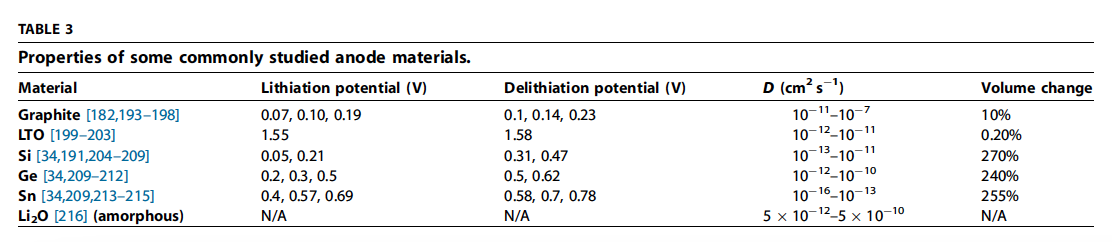

- Carbon has the combined properties of low cost, abundant availability, low delithiation potential vs Li, high Li diffusivity, high electrical conductivity, and relatively low volume change during lithiation/ delithiation (Table 3).

- Thus carbon has an attractive balance of relatively low cost, abundance, moderate energy density, power density, and cycle life, compared to any other intercalation-type anode materials.

- Graphitic carbons have large graphite grains and can achieve close to theoretical charge capacity. However, graphitic carbons do not combine well with a propylene carbonate (PC)- based electrolyte, which is preferred due to a low melting point and fast Li transport.

- During Li intercalation, single crystalline graphitic particles undergo uniaxial 10% strain along the edge planes. Such large strain may damage the SEI and reduce the cell’s cycle life.

- Hard carbons have small graphitic grains with disordered orientation, and are much less susceptible to exfoliation. These grains also have nanovoids between them, resulting in reduced and isotropic volume expansion.

- Nanovoids and defects also provide excess gravimetric capacity, allowing capacity in excess of the theoretical 372 mAh g1. Together, these properties make hard carbons a high capacity high cycle life material.

- However, the high fraction of exposed edge planes increases absolute quantity of SEI formed, reducing the coulombic efficiency. Also, the void spaces significantly reduce the density of the particles, further decreasing volumetric capacity.

- Finally, impurities such as hydrogen atoms can also provide extra capacity in carbon based anodes.

Lithium titanium oxide

- \(Li_4Ti_5O12\)(LTO) has been successfully commercialized because it allows the combination of superior thermal stability, high rate, relatively high volumetric capacity, and high cycle life, despite the higher cost of Ti, the reduced cell voltage, and lower capacity (175 mAh g1 & 600 mAh cm3 theoretical).

- High rate and stability originates from a ‘‘zero strain’’ intercalation mechanism in combination with a high potential of lithiation. LTO is considered ‘‘zero strain’’ because the phase change caused by lithiation/ delithiation only results in a slight (0.2%) change in volume.

- In addition, a high equilibrium potential (1.55 V vs. Li/Li+) allows LTO to be operated in a potential window above 1 V, largely avoiding the formation and growth of the anode SEI, which can slow Li inser-tion and induce Li losses in graphite anodes (Table 3).

- Even when an SEI is formed, the lack of volume change enhances the SEI’s stability. Since SEI impedance is not an issue, LTO nanoparticles can be used, similar to intercalation cathode material, which lead to higher rate performance at the expense of lower volumetric capacity [225,226]. In addition, LTO is extremely safe because its high potential prevents Li dendrite formation, even at high rates.

- Unfortunately, surface reactions are not completely avoidable with LTO anodes. LTO suffers from severe gassing due to a reaction between the organic electrolyte and the LTO active material [227]. This reaction can be suppressed by carbon coating, but carbon can also catalyze and accelerate electrolyte decomposition in the formation of an SEI, especially at high temperatures.

Conversion materials - alloying materials (Type B)

- alloying materials’ refer to elements which electrochemically alloy and form compound phases with Li (i.e. Type B conversion materials as in Eq. (2)) at a low potential (preferably below 1 V). Alloying materials can have extremely high volumetric and gravimetric capacity, but are notorious for their colossal volume change, expanding to several times the original volume upon lithiation (Fig. 6c illustrates how this occurs for Si).

- This can cause particles to fracture and lose electrical contact. For anodes, volume change can destroy the SEI protective layer, resulting in continuous electrolyte decomposition, loss of Li inventory and increasing cell impedance.

- Alloying anodes thus generally suffer from short cycle life due to the loss of active material and increasing cell impedance, especially at high mass loading.

- In general, the most successful strategy has been to produce a carbon composite in which the particles of alloying material have sufficiently small dimensions for mechanical stability, electron transport, and Li transport, while maintaining Li diffusion paths within the electrode(which commonly requires a hierarchical structure such as Fig. 2b )

- To stabilize the SEI, the active material can be encapsulated in a carbon shell with a sufficient void space to allow for volume expansion (Fig. 2e)

- Electrolyte additives can further stabilize the SEI and prolong the cycle life [242–244], and binders which bond to the active material, have high stiffness and swell minimally in electrolytes can provide additional mechanical stability if a carbon shell is not used.

- Si has received the most attention due to its relatively low average delithiation potential, extremely high gravimetric and volumetric capacity, abundance, lost cost, chemical stability, and non-toxicity

- Sn has also been of high interest, having similar properties except with lower gravimetric capacity, slightly lower cell voltage, but higher electrical conductivity. However, Sn appears to suffer from easy fracturing (Fig. 2a).

- Ge does not fracture even at larger particles sizes [251,252], but is too expensive for most practical application (Fig. 1a). Ga also has an interesting property of being liquid near room temperature [253], but is again too expensive.

- Of the cost effective Li alloying metals, Zn, Cd, and Pb have good volumetric capacity, but suffer from low gravimetric capacity.

- Al also suffers from severe fracturing even with nano dimen-sions, as confirmed by in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

- P and Sb have received some attention in recent years. Both elements have good capacity, and well performing electrodes have been constructed by merely ball milling the material with carbon [255,256]. However, both elements are toxic, have rela-tively high delithiation potentials.

Conversion materials

- Initial strategy is to use oxides in which Li2O are formed on the initial charging of the battery. The Li2O acts as a ‘glue’ to keep particles of the alloying material (such as Si or Sn) together, while also reducing the overall volume change within particles.

- But, Li2O has low electrical conductivity, and this approach inevitably results in a large irreversible capacity and a large voltage hysteresis, much of which remains even at extremely slow rates.

- Alter-natively, the Li2O itself can be used as an active material if the voltage range is significantly widened, enabling the use of non-alloying transition metals (such as Manganese(II)Oxide, Fig. 6d). This reduces the first cycle capacity loss and increases the charge capacity, but has the obvious issue of further reducing the poten-tial difference with the cathode.

Conclusion

- Yet research continues on new electrode materials to push the boundaries of cost, energy density, power density, cycle life, and safety. Various promising anode and cathode materials exist, but many suffer from limited electrical conductivity, slow Li transport, dissolution or other unfavorable interactions with electrolyte, low thermal stability, high volume expansion, and mechanical brittleness. Various methods have been pursued to overcome these challenges, as summarized in Fig. 3.

- Many intercalation cathodes have been brought to market, and conversion material technology is slowly coming closer to a widespread commercialization. As new materials and strategies are found, Li-ion batteries will no doubt have an ever greater impact on our lives in the years to come.